Donate

Please consider supporting our efforts to preserve Garland's history by donating here:

See More

Commerce and Industry

Commerce and Industry

- Details

This article originally appeared in the Garland/Mesquite section of The Dallas Morning News on July 7,1995.

By Michael R. Hayslip

For the Garland Chamber of Commerce, which marks its 100th anniversary this year, the business at hand was not always just business. As the first group organized for general civic betterment, its membership flourished in the city’s civic, cultural and social core as well.

Originally named the Garland Commercial Club, the chamber traces its birth to 1895, the year the U. S. Patent Office issued its first patent for a gasoline-powered automobile. It was also the founding year of Garland’s first commercial bank, the Citizens’ National, and the locals believed it was high time to spread the good word about Garland.

In his 1912 Silver Anniversary edition, Garland News publisher W. A. Holford, himself an ardent Commercial Club booster, touted the area as “. . .the best country, inhabited by the best people on the American continent.” After a brief suspension of activity during WWI, the club reorganized in 1919, and Holford reported that every business in town had resubscribed its membership, “save one or two,” whose names he disdainfully ignored.

Alternating luncheon and business meetings, the Commercial Club assembled monthly, but usually suspended formal activity for three months of the summer’s heat. Farmers, whose efforts produced the bulk of Garland’s income, were also invited to the meetings, which featured both local and out-of-town speakers on topics of general interest.

While the 19th amendment to the U. S. Constitution gave women the right of universal suffrage in 1920, Commercial Club membership in the early decades was a “men only” affairs. There were, however, efforts to make the group inclusive. Wives of the members provided food and suitable entertainment to augment the speaker presentations, which were subject to immediate newspaper criticism if they proved too lengthy or controversial.

With growing vigor club members tackled city-wide causes. They joined political leaders in 1921 to lobby successfully for rerouting the planned Bankhead Highway (State Highway Number 1) through the middle of the business district. In 1923 they changed the group’s name to Garland Chamber of Commerce, adopted the slogan “where teamwork works” and staged a community fair which attracted over 7,500 visitors to the city of 1,500.

By the late 1930s chamber leaders joined city and local banking officials in hot pursuit of industrial payrolls to stimulate growth and broaden the city’s tax base. Firms such as Craddock Foods, Byer-Rolnick Hat Corporation, Southern Aircraft Corporation and Guiberson Diesel Engine Company provided trophies from that early hunt, and many of their employees wove themselves indelibly into the fiber of the community.

Post-World War II chamber activity, propelled by the employment in 1947 of its first full-time paid executive manager, claimed responsibility for installations by Emsco Derrick, Luscombe Aircraft Company, International Rebuilders, Varo Inc., and Kraft Foods, which occupied the plant originally built by Guiberson. During the l950s the new addresses included spots for Hermetic Seal Transformer, Desoto Paint, Safeway Warehouse, Sherwin-Williams Inc., General Motors Training Center, Oil Well Supply and Globe Union Inc.

The cumulative effect of these corporate locations, combined with the establishment of feeder firms that supported them, was reflected in the Garland’s population, which roughly quadrupled during the decade of the ‘50s.

Concerns with the quality as well as the quantity of local life led to the formation of an adjunct chamber committee which by 1963 had secured land and funding for Memorial Hospital of Garland, now Baylor Garland. Such was the force of business and professional women by the 1970s that they began serving as chamber officials, and to date more than a dozen have filled officer and director chairs as the Garland Chamber of Commerce climbed into its maturity.

The available land space is mostly filled now, and Garland can no longer swap many cotton patches for industrial plants housing developments, but its Chamber of Commerce still faces challenges in helping to facilitate solutions and improve the quality of life in the city. That, after all, has always been the goal of “. . .the best people on the American continent.”

Photo caption:

A group of Garland business and professional men gather (ca. 1905) to salute one of their own on the eve of his wedding. Included are (l-r) John Beaver, Erle Embree, Gus Harris, unidentified, A. R. Davis (standing), Joe Harris, Walter Jones and Joe Pendergast. The groom’s vacant chair was for G. L. Davis, who served in the early ‘20s as president of the Garland Commercial Club, predecessor of the Garland Chamber of Commerce.

- Details

This article originally appeared in the Garland/Mesquite section of The Dallas Morning News on November 3,1995.

By Michael R. Hayslip

In the late l960s the management of Garland’s Varo Inc., was up in the air about specialized rapid transit needs.

Heavily involved in defense contracting for all of its corporate life, Varo’s leadership wanted to diversify their product mix. Among their considerations was the possibility of developing and manufacturing a world-class rapid transit system, whose components would utilize some of the company’s existing strengths. They believed that they could successfully market a concept--monorail--whose time had already come.

As ombudsman for the project Varo recruited E. O. Haltom, who had promoted the monorail idea for several years, but lacked the manufacturing capability to complete a system. Haltom worked alongside W. J. “Joe” Holt, the Varo vice president in charge of research to assemble a development team. Together they refined the “Monocab” concept for a weatherproof installation so versatile that it could automatically run not only between, but also inside of buildings. Varo president Jack Smith romanced the press with the term “elevator.”

Varo’s first serious prospect was the Dallas-Ft. Worth Regional Airport, but officials there were skeptical of a bidder with no prototype for an example. Undaunted, the Garland Monocab team staked out a spot on the company’s 150-acre Walnut Street campus and built a model in less than 30 days. The overhead rail was a single section which began at a loading station and terminated in mid-air 50 feet away, where a ladder was available in case of emergency.

With a $1 million grant from the U. S. Department of Transportation, the Airport Authority funded two $350,000 development studies. Varo, which had now been joined by the E-Systems predecessor LTV, received one of the study awards for an overhead monorail system. The other award went to a company whose vehicles crawled on the ground.

Near the first model, the Varo/LTV team erected a full-scale, closed-loop example of their system, now officially trademarked ”Stratoline.”

But in 1971, when the smoke cleared from the bid opening, both bids had been thrown out as too high. Unable to continue the uphill battle, Varo withdrew to lick its wounds. LTV, however, pursued the contract on its own and eventually won the airport contract with a proposal for automated four-wheel vehicles, which still operate today.

Varo then sold its Monocab Division to Rohr Industries, Inc. of Chula Vista, California. Rohr, which had completed metropolitan transit systems in San Francisco and Washington, D.C., operated the Monocab Division on its original Garland site until 1974, then transferred it to California. Holt, who was and still remains committed to the monorail concept, left Varo with the division to join Rohr as vice president.

After several unsuccessful attempts at other installations, Rohr later shelved the transportation effort to concentrate on other lines. Holt moved on to the Department of Transportation in Washington, D. C. After acquisition by Imo Industries in the late ‘80s, Varo, Inc. became Varo/Imo. LTV evolved into the present E-Systems.

Photos courtesy W. J. Holt.

Varo Inc.’s Monocab, conceived in the late ‘60s as a light, single-rail, overhead, weatherproof public transportation system, functioned as a “horizontal elevator.”

- Details

This article originally appeared in the Garland/Mesquite section of The Dallas Morning News on April 28, 1995.

By Michael R. Hayslip

One of Garland’s worst-kept secrets after the close of World War II was the flying car project at Southern Aircraft Corporation. Almost everybody in town knew about it, but not much.

Originally designed by Theodore Hall, an engineer at Consolidated Aircraft in California, the car was built, flown and driven there before the war as a prototype. Though sidetracked by defense production needs, the concept stuck in the mind of Willis C. Brown, president of SAC, which supplied tail and nose turrets for Consolidated’s B-24 bomber.

Brown was intrigued by the possibility of a general-purpose passenger car that could accept wings, tail and propeller available for temporary attachment at a neighborhood airport. The driver/pilot could spin around town on rubber-tired wheels or take to the air for longer hauls, checking in his attachments at the destination.

After the war’s end in 1945 the car and its wings quietly arrived at Southern Aircraft’s Garland plant, which needed products for peacetime production. SAC had agreed to complete further development on the vehicle, called the “Roto Mobile” within specific time lines; otherwise, it would be returned to California. Meanwhile, a photo of the car had appeared on the cover of LifeMagazine.

Behind closed doors, work resumed under the direction of Orin Moe, a veteran SAC engineer, who ordered certain modifications. E. M. Johnson, Jr., another SAC engineer working simultaneously on development of a twin-engine plane, recalls that engine power was a concern for both projects. Nevertheless, the flying car was eventually driven to Majors Field in Greenville, where employees saw it fly briefly.

Renamed the “Southern Roadable,” the little two-seater machine resembled an 1,800-pound locust with a 30-foot wingspan. Top airspeed was 128 miles per hour, with a cruising speed of 110. When driven as an automobile, its rudder controls activated the clutch and brakes.

Due in part to financial strains and changes in ownership three years after the war ended, Southern Aircraft failed to complete its commitment on time, and the modified prototype was returned to California as agreed. Since its west coast originators eventually abandoned the project, the flying car was acquired by the San Diego Air Museum, where it remained on display until destroyed by an arsonist’s blaze in 1979.

Meanwhile, Southern Aircraft became Intercontinental Manufacturing Company, or IMCO, a name retained today through six successive ownerships since the original group headed by Brown. Though the succeeding owners never attempted another flying car, IMCO has distinguished itself by producing bomb bodies, rocket motor cases and precision products for aeronautical and space needs.

The flying car, seen around Southern Aircraft after WWII.

- Details

This article originally appeared in the Garland/Mesquite section of The Dallas Morning News on April 21, 1995.

By Michael R. Hayslip

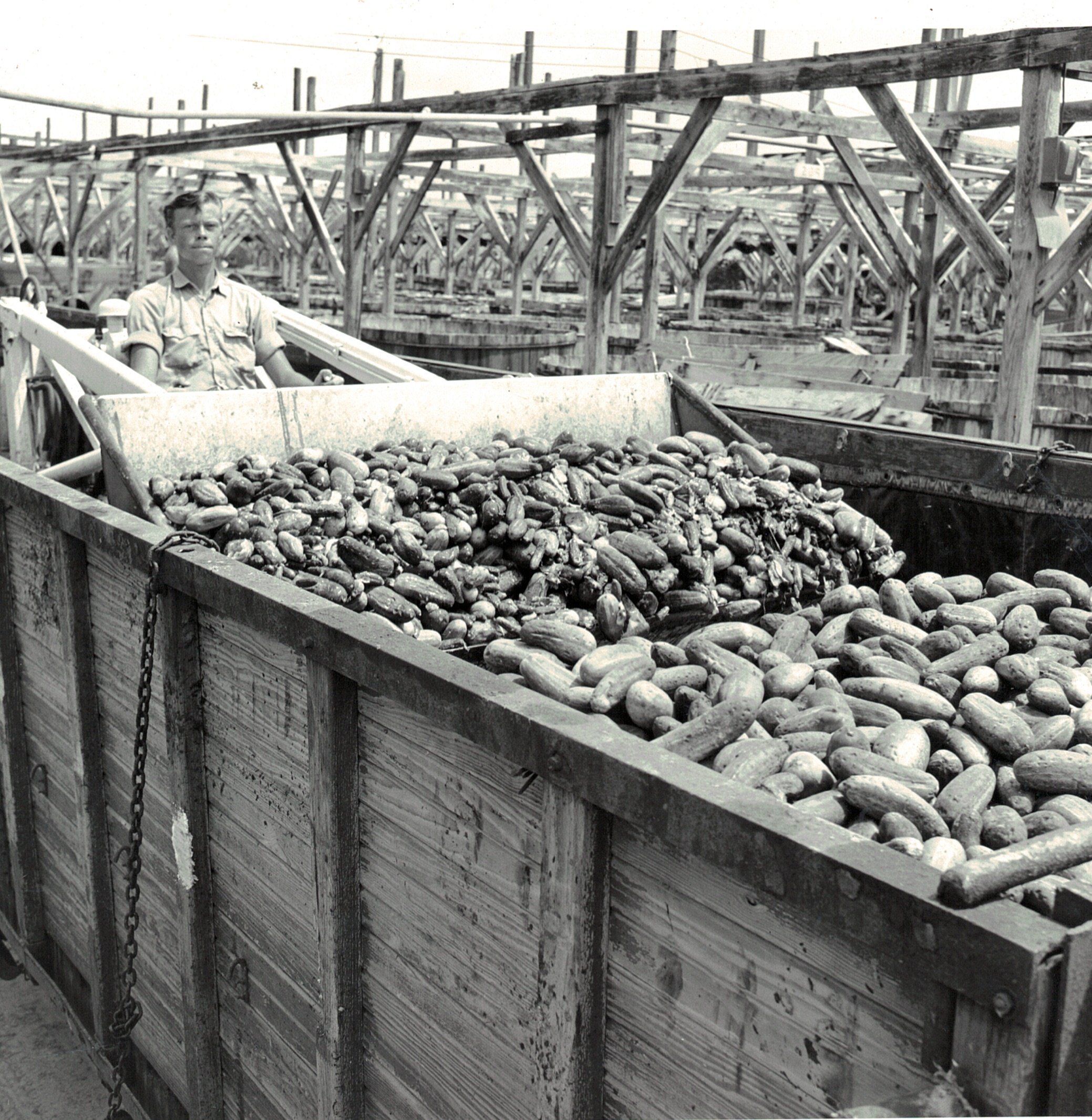

In one way or another Joe Craddock’s pickle factory turned everybody’s head when it to moved from Dallas to Garland in 1937.

The $50,000 annual pickle payroll provided plums to pay the pipers of workers, businesses and their taxing authorities during lean times of the Depression. Utilizing the old facilities of the Garland Cotton Oil Mill beside the Katy tracks, the Craddock Food Manufacturing Company plant adjoined the Ferris Watson Seed Company installation to form an agribusiness industrial district at the north end of town -- Walnut Street.

Into this plant Craddock hauled pickling cucumbers, grown in various parts of Texas and Oklahoma for processing into dill, sour and sweet pickles, as well as relishes, marketed under the brand names of Betty Brand, Crispy and Crown .

On arrival the cucumbers were soaked in wooden vats with a brine of salt and water to create a “salt stock,” which could be processed into various flavors. After this initial step, which required at least six weeks, they were transferred to a series of other vats, containing vinegar for fermentation, alum for crispness, tumeric for even color and various flavoring spices for the desired effect..

According to Ralph Hammerle, “brewmeister” at the plant throughout the ‘50s, Craddock eventually boasted the world’s largest storage capacity, employing up to 40 full-time employees. In season, employment doubled.

More significant to some was the acrid aroma that drifted from the vats, averaging 700 bushels each, where tons of cucumbers lay in silent wait to become full-fledged pickles. Although some of these vats had been acquired from Anheuser Busch, their odor was not of beer, but of microorganisms produced by the pickle-making process. Carried along by prevailing southerly winds, this scent reminded everybody but Mr. Craddock, who lived in Dallas, that Garland was in the pickle business.

Had the vats remained open to the sky, sunlight would have diminished the stench and altered the character of the neighborhood. But rain would have also diluted the pickling solution, requiring frequent adjustment; therefore, the vats were covered as a matter of convenience.

Despite the malodorous aspects of the plant, as well as vat discharges onto open ground, new residential subdivisions were soon built north and west of it to alleviate the housing shortage caused by World War II. Grumbling, but grateful for a place to live, families quickly filled the homes. Some of them remained there until Morton Foods acquired the plant in the ‘60s and siphoned pickle production to their plant in Carrollton.

The pickle factory was razed to make room for Garland’s Main Post Office, dedicated in 1976. Soil tests prior to construction confirmed the historic account that the Post Office is perhaps the only one in the nation floating upon three decades of salt brine and pickle juice.

Photo caption:

A worker unloads cucumbers at the Craddock pickle plant, located where the Main Post Office now stands at Walnut and Newman Streets. (About 1945)

- Details

This article originally appeared in the Garland/Mesquite section of The Dallas Morning News on June 2, 1995.

By Michael R. Hayslip

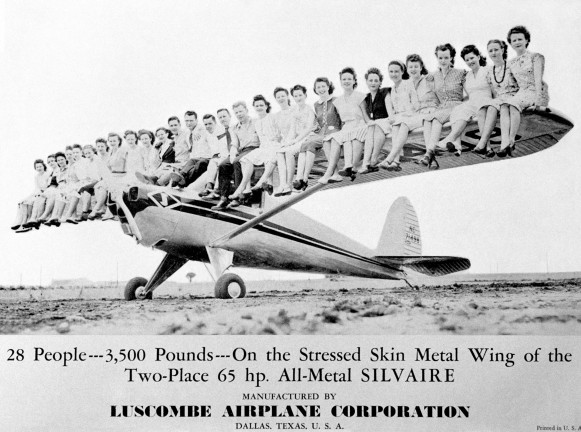

With all the effort Garland manufacturers have invested in aeronautical pursuits, Luscombe Airplane Corporation is the only one that ever successfully marketed and mass produced entire airplanes.

Originally located in Kansas City, the firm was created in 1935 as Luscombe Airplane Company under the leadership of Don Luscombe, an aircraft enthusiast who dreamed of designing and building personal light planes. Leopold H. P. Klotz acquired control in 1938.

Headquartered in Trenton, New Jersey during World War II, the company converted its production to military wares, principally on Navy prime contracts for airframe parts, such as armaments and fuel tanks.

When the war ended, Klotz began searching for a better location to resume and gear up peacetime production of Luscombe’s all-metal personal plane, the Silvaire. Requirements for the new site included better flying weather, more pilots, broader labor market, lower wages, and cheaper building costs than Trenton, plus a railroad siding and room for a landing field.

A 500-acre tract of prime farming land was chosen on Jupiter Road, absorbing most of a quadrant bounded by Forest Lane to the north, Shiloh Road on the east and Miller Road on the south. Groundbreaking for the plant occurred in April of 1945.

Slowly but surely the plant buildings took shape, and by the end of the year contractors completed the parking lot, which relieved parking on either side of Jupiter Road. Later the familiar checkered water tower arose and was used with the Luscombe well to augment city water supplies during a severe drought in 1950.

Of the 6,000 Silvaires (or Model 8's) ever built, 4,000 came from Garland. Selling for $2 to 4 thousand dollars, these planes provided work for up to 1,250 employees, who cranked them out at a peak rate of 21 units per day.

Besides a payroll Luscombe assembled a cadre of employees who became familiar fixtures in the Garland community scene. The planes they produced had staying power as well, and that today the FAA maintains registration on more than 2300, which command prices of anywhere from $15 to 25 thousand each.

Nevertheless, market demand of the day failed to meet expectations, and by 1950 the company was bought in receivership by Texas Engineering and Manufacturing Company (TEMCO). Although 50 more Silvaires were built afterward, production shifted to parts and assemblies for various military and commercial aircraft.

With the merger of TEMCO and Ling Electronics in 1960, the operation was called Ling Temco Electronics. The purchase of Chance Vought in 1961 changed the name to Ling Temco Vought (LTV). Under that structure modified forms of LTV were used until 1972, when the plant was spun off from LTV to become the E- Systems, now known as the Garland Division of E-Systems.

Merle Mueller, a retired veteran of the original Luscombe crew, has maintained historical files on the company and information on Luscombe employees from 1945-1949. He now circulates an “almost nearly periodic” newsletter among the group.

Photo Courtesy of Merle Mueller